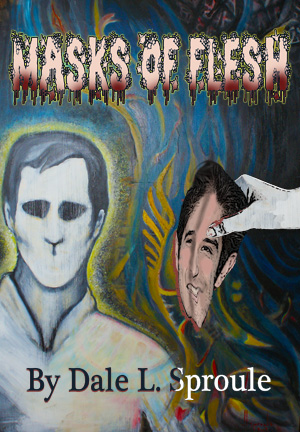

Masks of Flesh

by Dale L. Sproule

My father was a brilliant man, a professor of anthropology, but after seven years of his constant company, I understood why so many of his peers in the pre-madness world considered him a crackpot.

Not that his ideas were bad. Just unorthodox. Take the “scarecrows”.

“What do you think of this?” Dad strode into the kitchen, carrying a huge tome in his good arm. Thumping it down in a valley between stratified mountains of books on the big oak table, he flipped it open, arraying candles on plateaus of literature. Theatrically running his long fingered hand through his eroded thistlehead of white hair, he beckoned us with the other hand.

My sister, Jan and I were standing at the kitchen counter with bowls of steamed carrots; me craving the taste of butter and remembering a time in my childhood when we would slather it on our food. Jan couldn’t remember dairy products. In fact, a teenaged friend of hers at Windsor Stronghold had told her that milk and butter and cheese were the stuff of old wives tales; the notion of any animal allowing us to take its milk, as plausible as Santa Claus. Setting her bowl on the counter, Jan crossed the kitchen and leaned over the table.

A woodprint of bodies impaled on poles filled the top half of the page. Below it was a paragraph describing the legendary practices of Vlad the Impaler as landmarks in the psychological history of intimidation. I read aloud, “‘Vlad’s methods held off the Turkish army until it became apparent to everyone that his own history of torture and imprisonment had turned Vlad into a complete madman.’ What does this have to do with us?”

“He held off the Turks, it might keep raiders away from the potato patch,” Dad said.

“Heads on poles went out of style ages ago, ” I said. “We’re supposed to have become a bit more civilized in the past 600 years.”

“In the 1970’s,” Dad whispered. “The Khymer Rouge built towers of human skulls. And that was back when we were still trying to pretend we were civilized.”

I walked to the window, opened the shutters and looked out on our mountainside. Where our neighbours had once lived, terraces of glass shone in the moonlight like misshapen white spaces on a giant chessboard, greenhouses built out of salvaged glass over the foundations of the houses we had torched.

Human raiders had done more damage to our crops over the past the few months than animals had ever done.

I looked back at Jan and Dad. “How do you propose to do this? Want me to go over to the stronghold to find a few people who wouldn’t mind being butchered for a worthy cause?” I asked.

“Something like that,” Dad said with a smile.

The next day he took us to a place outside of Tillicum Stronghold, which had once been a shopping centre. When people had moved into the old mall, they had cleared out the refuse. The unburnable mannequins had been stacked in a mass grave and forgotten.

Two days after he seeded the idea, I was driving 8 foot wooden stakes through the lower backs of one-after-another of our ‘signposts.’ Around me on the mountainside, the still air reeked of molten plastic. I poured red paint over the points protruding from their chests and necks, flowing the blood-red paint down, to gush convincingly over the torsos. The shafts were tapered, so that the bodies locked into position half a metre off the ground. When I couldn’t get the arms to flop back the way I wanted, I broke them with a crowbar. The hands and the fingers too. Then I wired the pieces together.

“Nice job, Picasso,” Dad said, coming up behind me. “Can’t tell they’re not real unless you get real close. Reminds me of the Ice Capades.”

“What are Ice Capades?” I asked.

“Like ice dancers, you know?” Then he laughed, “Who am I kidding, that’s almost before my time.”

“Danse Macabre,” I suggested

“That’s the spirit,” Dad laughed. “A message only a malice-puppet could ignore.”

Malice-puppet was a name Dad made up last winter, after Grant Petersen came pounding at our door. We let him in figuring his wife or one of the kids might be in trouble. He swung at Dad with a hatchet, planting it deep in his arm before I shot Petersen in the head. Found out later that he’d butchered his family before coming to take care of us.

Dad survived, but developed the habit of carrying a handgun in his bellypouch. If he pulled it out and you ran and hid like most people would, he accepted it as proof that you weren’t a malice-puppet and (usually) let you live.

“They look like they were once alive. You’re a natural artist, Mark. I just wish we lived in a world where there were a few more practical applications for your talent.”

Forgetting that my hands were covered in paint, I reached out to straighten the mannequin’s wig. My fingertips slid down my victim’s cheek leaving crimson claw marks.

My hand was shaking as I drew it back. I was too fixated on the face to hear what Dad was saying. It reminded so much of my mother’s face. I hardly ever thought or dreamed about her anymore, but in that instant, it all came rushing back: the bus window splattered with spring mud; me squeezing past Mom into the narrow aisle; Mom gliding up behind me as the door hissed open; me running ahead through wet leaves; Mom’s shriek of alarm; me looking back, unable to see her face through a blur of flapping wings and splattering blood. Talons were tearing at her hands, a beak spearing at her eyes. I panicked and ran toward her. It gouged at me too. I remember handfuls of feathers, a tiny ribcage cracking underfoot. A Samoyed that belonged to one of the tenants came bounding across the driveway, hitting Mom from behind, not making a sound until it was tearing at her throat. I remember the weight and coarseness of the chunk of broken concrete I found in my hand, the relentless rhythm of my arm swinging down and down into a pile of bloody fur still whimpering. I remember the odd, moist texture of Mom’s green sweater as I put my hands on her shoulders and shook her, looking for life. I don’t remember passing out but my next memory was in the hospital.

They kept me there overnight after the attack that killed my Mom; stitched me up, wrapped the hand with the two broken fingers and released me. The emergency ward was filled with the survivors of animal attacks. I remember one man swearing there were several raccoons and a housecat in the pack of dogs that had nearly killed him.

By the time people clued in enough to start putting their beloved pets to sleep, old Rover often managed to wipe out entire families. And the death rates kept climbing. When the domestic animals were all dead, the wild ones moved in. Then the insects. Mosquitos, wasps and locusts. Pestilence-a-plenty. Ninety-four percent of the human population was wiped out over in 36 months. Concrete barricades were built around apartment blocks, that reconceived themselves as strongholds. The strongholds took down all the trees and burned down all the empty houses in their neighbourhoods. They rounded up all the bullets and gasoline and pesticides.

As natural pollination became rare, starvation grew common. Strongholds became serfdoms. Dad said they were all ruled by nasty little fascists who thanked their individual Gods every night for the Madness that had given them power that otherwise would have been out of their grasps forever. Dad was even more eloquent on the subject of the strongholds than he was on most things.

We stayed in our house, reinforcing and fireproofing it. Dad described the house once as Beaver Cleaver’s dream fort – 50’s suburbia in full battle armour. Under layers of plywood and sheet metal, you can still make out the shape of a big, gabled split level home, like a bottle in decaying Christmas wrap.

Once I started thinking about the past, I got lost in the fugue for the rest of the afternoon. Astonishment and fear had long since turned to tedium and bitterness. So, I was in a black mood when Dad came in, chewing vigorously on a piece of dried meat. The upper plate of his false teeth had broken in half a few weeks earlier and we still hadn’t found new ones or a way to fix the old ones. “I need you to get that old car battery from under the workbench in the garage.”

Here we go again, I thought. It was the third time in as many years he’d sent me to look for this thing that didn’t exist. Neither Jan nor I remembered ever having seen it, but arguing with him would be putting off the inevitable, so I took my time, made a show of it. That way he wouldn’t be pissed off when I came back empty-handed.

When I returned he spoke before I had the door half-opened. “Nothing, eh?”

“A box of shirts.”

“Shirts?”

“Yeah. Those red plaid flannelette shirts Uncle Vern used to wear all the time.”

“Did you bring them in?”

“What for?”

“Might be able to trade them for batteries or something.”

I rolled my eyes. Batteries were almost as hard to come by as gas. But there was no sense challenging Dad when he set his mind on something.

Jan modelled one of the huge shirts for us. I laughed at the time, but Uncle Vern haunted my dreams that night, coming back from the dead to tell me his secret; that he was a demon, elaborately disguised in an enormous fat suit. And he told me that I was a spy, programmed to fool everyone including myself, right up to the crucial moment. It made perfect sense in the dream, since I’d always felt different from those around me – an outsider, even from other family members, although I couldn’t imagine ever betraying them.

I looked at Uncle Vern and screamed, “You’re a liar!” But he was already gone.

I touched my face. The skin was numb. I dug my fingernail into the flesh of my cheek. It didn’t hurt. I pushed harder, twisting it like a drill and sinking it in up to the first knuckle, then pulling and prying at the area around the hole. My face split in two. Peeling off first the top half and then the bottom, I gazed in terror at the bisected face. I held a stare in my right hand and a smile in my left.

There were no mirrors to show me what I looked like underneath the mask.

The lips of the mask moved, began to form words. “Traitor,” they said.

The next morning, I sat up in bed with my eyes closed, trying to fill out the foggy patches of the dream.

“I’m taking those shirts to Viewtower instead of Ocean Point.” The sudden conversation startled me. I turned to see Dad rooting through the cupboards behind me. He reached for the jam, the one jar of strawberry from the cupboardful of home preserves we’d scavenged during our Colwood trip the previous summer. We were all getting sick of plum.

“We should get going soon regardless,” I said.

Dad glanced at me and said drily. “You’re not coming.”

“You’re not going alone?”

“No, Jan’s coming.”

“She went last week!” I protested.

Swallowing a large spoonful of jam, Dad said in his don’t-mess- with-me voice, “I need you to dig potatoes.”

We’d planted over a dozen patches, each small enough that other scavengers wouldn’t be likely to find them.

“Why can’t she do it? It’s not like there isn’t a map! It’s even colour coded, with planting and harvesting dates, so she can’t screw it up!”

Jan stuck out her tongue as Dad countered, “You know where the plots are, Mr. Atlas. And we need someone with a strong back to roll them up here. So, fill the damned bin before the raiders realize our wall of death is all bluff and attack us in force. I need Julia Child here with me.”

Dad put on his jacket and stuffed several pieces of rabbit jerky into a pocket, before hoisting the Browning automatic down from the wall rack. He checked the magazine, plucked some fresh shells out of the box in the hutch and dropped them into the same pocket as the meat, then slung the bundle of shirts over his shoulder with the extra rope we’d tied on for that purpose. Turning without looking at us, he marched abruptly out the door.

“You got a boyfriend at Viewtower? How did you talk Dad into taking you again?”

“Maybe I do,” she said as she hurriedly got on her own coat and followed. Before she pulled the door closed, she said, “Cheer up, idiot. It’s your birthday on Friday. He doesn’t want you to see what you’re getting.”

“Oh, c’mon. We don’t have enough to trade for gas and food, why would he get me a present?”

She looked at me as though I’d left my brain in the garage the night before. Dad hadn’t neglected a birthday yet. Somehow, they had become more important.

So I got to dig potatoes and haul them up the mountain by myself. Nice birthday present, I thought as went to the living room after working all day.

Jan had left an old science book open on the couch with instructions for making something called a crystal radio. The accompanying article explained how they worked without batteries or electricity.

I thought of making one myself until I realized that it was probably going to be my gift from Jan. It would serve her right if I beat her to it, I laughed to myself.

Right around when I started feeling guilty for wasting so much time, the back door slammed open and Jan screeched, “Mark! Are you still here? We need you!”

That was a mighty strange statement coming from my sister! I jumped up from the couch and ran to the kitchen.

She actually looked relieved to see me. “It’s Dad. He’s hurt bad.”

“What? How? Where?” I asked without giving her a chance to answer.

“He collapsed at the bottom of the mountain. He was losing a lot of blood.”

“What? Did he get shot? Attacked? What’s going on?”

“I think he stepped on something,” she answered all the questions at once, but vaguely. She hauled on my coat sleeve almost pulling me over while I put on my boots. “I didn’t see it happen. Now hurry!”

I saw a crumpled shape in the middle of the road about hundred metres distant.

“Where’s your gun?” I asked, putting my arm around his waist and pulling him to his feet. Dad’s usually strong hand feebly grasped the fabric of my shirt.

“Dropped it,” Dad muttered, barely coherent.

“Where?” I insisted. We couldn’t afford to lose our best rifle. He didn’t answer. Jan got there a second later. Even with both of us propping him up, it took several minutes to get him into the house and lay him down on the couch.

As I began unlacing the boot, Jan came in with a bowl of water, some bandages and

disinfectant. When she saw how serious it was, she said, “Don’t take it off yet, I’ll get some towels.”

But I wasn’t listening. As I pulled off the boot, my father screamed and kicked with his injured foot, pushing me to the floor.

“I told you to…oh, Jeez,” Jan cried. She wrapped a towel around the foot and applied pressure from underneath. Our father screamed and writhed then abruptly stopped struggling.

I couldn’t find his pulse, so Jan took his wrist and immediately sighed. “You’ve gotta learn to do this better. She nodded. “He’s alive.”

I held a finger under his nose and felt his warm breath, then lifted one eyelid.

“What are you doing?” my sister asked.

“Aren’t you supposed to be able to tell something from that?” I muttered as I pulled my hand back.

“So, what, exactly, can you tell?” she asked.

“His pupils are dilated.”

“Yes? Telling us what, exactly?”

I stood up and yelled, “I get it! But what was I supposed to do? How can I help him?”

She stopped and said, “I think there’s something in it. Big nail or…something.”

She inserted her finger into the wound and pulled it back as though it were an electrical socket. “It’s quivering. Like it’s alive.”

“Bullshit.” I didn’t want to think about what this might mean. I had never seen a malice worm, but like everyone, I knew what they were supposed to look like. Less worms than snails in slender conical shells that were needle sharp on one end and widened to the diameter of a man’s thumb at the other. The same size as the hole in Dad’s boot. They were rumoured to travel underground like clams without the seaside.

“Were you with him when it happened.”

“Let’s talk about this later. I need tweezers or something.”

“Where do you keep them?” Then I thought of an alternative and said, “Oh, nevermind.”

I came back a moment later with needle nose pliers, washed them with soap and water, then poured alcohol over them.

“Is there a cup you can soak them in?” Jan asked.

“Not a clean one,” I said and by the time I turned back, she was already digging in the wound.

I watched in terror. It simply couldn’t be a malice worm. It just seemed to Jan that something was quivering because Dad’s whole leg was trembling from the shock. Malice worms couldn’t move that fast, couldn’t attack someone like that. Could they?

By the time Jan came out empty for the third time, the blood was spurting. Jan lowered his foot back to the couch and pressed the sodden rag to the wound.

“You have to keep trying,” I said.

“I can’t,” she replied. “There’s nothing in there to grab. He’s bleeding to death. If I keep trying it will kill him. I don’t have the equipment or the knowledge. You asked what you can do? Go to Viewtower Stronghold.”

“Windsor’s closer. I’ll get Dr. White.!”

“They all went to fucking Viewtower to see the Breth. I saw Dr. White there.”

“The Breth is at Viewtower? What for?”

“How the fuck should I know? I was with Dad. He’d said he’d chop it into little pieces before listening to its lies.” she screamed. “Hurry!”

I tried to remember where I’d propped my .22 on the way into the house with Dad. I was just as worried as Jan. What right did she have to order me around? I was a capable adult. Certainly more of an adult than she was. I only obeyed because…she was right. We were out of our depth. I slammed the door on the way out.

If Dad wasn’t such a tightass with his rules we might have known what was going on. Why had the Breth come to our stupid freaking island of all the places on Earth?

A raccoon watched from a tree as I dashed past the stretch of wilderness at Kinsman Gorge Park. I ran to the middle of the bridge before turning around with my gun poised. But amazingly, it didn’t attack.

A few blocks later, a wasp zipped past, inches from my face. I froze, trying to track its trajectory. Where there was one wasp there were usually many. I could see no corpses along the curb or in the tall grass along the shore. Perhaps this wasp had simply strayed too far from its nest. I listened for buzzing and heard only the hiss and patter of tiny raindrops on leaves and grass.

Twenty minutes later, I reached the walls around the stronghold. Choking my way through a pesticide haze, I pounded on the front gate. The sentry was wearing a gas mask. She asked if I’d seen any wasps and looked relieved when I told her how far from the stronghold my sighting had occurred.

“I need Dr. White. Emergency. Do you know where he is?” I asked while walking backward into the courtyard.

“At the meeting in the main lobby most likely,” she said.

Through the big glass doors of the main apartment building, I could see a large crowd gathered. Good luck finding him in here, I thought. Inside the door, I came up beside a man who was all curly black hair and bushy beard. I tapped him on the shoulder.

“I’m looking for Doctor White, from Windsor Stronghold.”

The man shrugged.

“Where’s the clinic?”

He pointed down a hallway. “But it’s closed.”

I had to shout to be heard as the din of the crowd grew several notches louder, “There must be somebody on standby for emergencies!”

The man shrugged again and I leaned in and shouted, “Why is the Breth here?”

“You haven’t heard? It’s cleared out almost all the malice worms. It’s tracked the last of them here.”

A voice said over a loudspeaker, “Here’s Mayor Peter Shaver of Viewtower to introduce our very special guest.”

I’d never even seen pictures of the Breth, but I’d heard it described as a giant slug molded into a vaguely humanoid shapes. From across the room I could see that the description didn’t do it justice. The Breth was slightly taller and bulkier than the humans surrounding it – with the mottled colour and apparent texture of an overripe banana. It wasn’t wearing any sort of clothing.

The inanities coming out of the mouth of the Mayor melted to babble as I pushed my way through the crowd toward the Breth, with no plan other than getting a closer look. It seemed to have a human-like face, but instead of a skull, the back of its head looked like a half full sack of potatoes. Its fingers were almost as long as its stubby arms. Tyrannosaurus slugs, I thought. As I watched, the Breth grew a foot taller and as it did, its flesh seemed to become more translucent. I could now see that the face had two eyes but no mouth. Those eyes locked on mine.

Alien thoughts slithered into my consciousness.

The Mayor stopped talking. Everyone in the crowd turned simultaneously and looked at me.

“You have encountered the valent we are searching for.” The voice was a bagpipe drone, overlaid with a squishy whisper. And even as I heard the words, I realized that the alien wasn’t actually communicating in an Earthly language, that these words were supplied by my own mind, organizing the information and feeding it back to me in a format I could understand.

As the concept of ‘valents’ tried to form itself in my consciousness, it came with a whole host of confusing and contradictory definitions. The primary meaning seemed to be, ‘part of ourselves’, but it also meant ‘ambition’, ‘reward’, ‘beautiful aggression’, ‘your pestilence’ and simply ‘malice worms.’

“My Dad,” I said, “needs your help.”

“Your parent is beyond hope,” the Breth said. “But there are others we must save, are there not?”

“That’s Mark Hoag. Damon Hoag’s son.”

“You must guide us to the valent,” said the Breth as it slid down off the podium. “Now.”

“I know where they live!” someone shouted. “Follow me!”

Other voices rose up, “Yeah, let’s go!”

The crowd roared its agreement.

“Kill ourselves a malice worm!”

More comments were buried in pandemonium.

“Stop!” The Breth’s mental exclamation pummeled all other thoughts out of its path. “Only Breth can contain it. Terrestrial life-forms are too fragile. Anyone nearby is in danger. This human alone will guide me.”

As we left the building, nobody followed. I looked back twice more before we reached the already opened gate and nobody even stepped out of the building.

“What did you do to them?”

“Simply told the truth.”

“Why aren’t they coming out?”

“They know not to interfere.”

“Did you hurt them?”

“Not at all,” said the Breth, and I knew he was telling the truth. Those people would be fine. I took one last look and still saw no movement. Despite the Breth’s assurances, my stomach did a little flip. In fact, I realized, it was because of the Breth’s assurances.

Twisting the top part of its body like taffy, the Breth managed to convey the effect of cocking its head. “Are you not coming to rescue your family?”

“My Dad thinks you put the malice worms here to eliminate us, so you can use this planet to plant crops or whatever you do with planets you conquer. Why should I believe anything you tell me?”

“In our society, thoughts cannot be hidden, deceit is impossible,” the alien said. I felt the creature’s bewilderment and fascination with the concept of dishonesty.

“We must hurry,” said the Breth. “This valent is aware of our proximity – clinging to its autonomy.”

The alien moved faster than I, flowing as much as walking with a strange bipedal gait. I ran as fast as my already exhausted state would allow. Stopping several times to wait for me, it suggested, “We could carry you.”

“Don’t even fucking touch me,” I said as I slogged past.

“How distant is the victim?”

“You can read my mind,” I replied aloud. Then I simply thought the rest of the question, “Why don’t you tell me?”

“Spatial relationships are complex calculations for Breth. We require your navigational assistance.”

An hour later, I stopped, bending over with my hands on my knees as I gasped for breath.

The alien went on for a ways, then came directly back, stopping in front of me and regarding me with eyes like spinning black orbs. The more often it communicated with me, the more seamlessly its thoughts merged with my own. There was less a sense of being spoken to than simply understanding something. I could barely distinguish my own thoughts from the slithery voice telling me, “Speed is imperative. Your sibling’s life is in extreme danger.”

I can’t tell you how much it bothered me that it knew about Jan without my telling it.

I said, “I came here to fetch the doctor, not you. I don’t trust you?”

“Trust,” it said. “A peculiar human concept. You know as well as we do that we are here to help. The escape of the valents was a tragic accident. We are attempting to minimize the impact on your environment.”

“If you expect my help, then I need to know more about you.”

“A biology lesson is worth more to you than your sibling’s life?”

“She can take care of herself. She has the gun. Now tell me something about your kind.”

“You are impressively strong-willed to resist our imperative. If your sibling shares this trait, its survival is conceivable.”

The next conversation took place in a few seconds, because I barely had time to consider the questions before I knew the answers. Nothing was spoken aloud.

“You speak and think of yourself in the plural,” I observed. “Why?”

“In our natural state, Breth hosts are formless and listless. We eat, excrete, reproduce….”

I had a clear mental image of these things, like giant pancakes, lying together in a swamp, overlapping and rubbing together, but otherwise, not moving much at all.

“Our relationship with the valents is symbiotic,” explained the Breth. “We interact chemically, hormonally, mentally. We harness their rage and purpose and their valence completes us. Fuels our ambition, fills us with motivation, forces us to apply our intelligence. Through us, they can aspire to do more than simply drill through the muck and fill the air with the stench of their discontent. Within us, they are part of God’s own civilization.”

“And without you, they run around and kill things!”

“Without us, they are profoundly unproductive – toxic and acidic – and they find a savage joy in that.” The positive spin was restored immediately. “Through the valents, we gained the ability to communicate with one another – a path that ultimately brought us to the stars. When Batch 4320 Prime crashed on your planet, the host died and all of its valents escaped.”

I stared into its eyes which seemed deeper and darker than before. The spinning effect had all but stopped.

“The malice worms are a part of you?” I said.

“That is correct,” said the alien.

“How many valents did he have? This Breth that crashed.”

“We will discuss nothing more unless we resume progress towards the valent’s location.”

Rather than spinning around, the face simply melted into the Breth’s body and it started flowing away from me. As I ran up beside it, the Breth proceeded to answer my question. “Batch 4320 Prime contained two hundred and seventeen valents. Once orphaned, they each went their own way.”

“Spreading the Madness,” I said.

“Aggression is already abundant in the lifeforms that have evolved on your planet. Whenever the valents were able to establish any sort of mental interface, their own aggression served to increase the levels in the host, while the host’s aggression built up inside of the valent.”

Like a feedback loop, I understood.

“As the energy escalated, psychic fields filled with pure rage grew around them, affecting every impressionable creature within range. A frenzy that would not stop until the host died, setting the valent free, so that its search for a more compatible host could continue. Humans are only affected through direct interface, but they die quickly.”

The Breth stopped in mid-thought, rising up to a height of seven or eight feet. “We have arrived at your residence, have we not? I feel the valent nearby.”

“One more question. How many valents are inside you?”

“One hundred and seven when our mission began,” it said. “Plus one hundred and eighty two survivors from Batch 4320 Prime.”

All pretence of looking human was abandoned as it flowed rapidly up the hill.

“And if you were killed?” I hurried to get in one final query.

“Our valents would be free once more.”

As I stood staring at its receding shape, I wondered if I had done the right thing bringing it here.

“You don’t believe the Breth’s bullshit, do you Mark?” Dad’s voice came from the air itself. I looked around but couldn’t see him. “You know they don’t really care about you.”

“Dad?” I turned in a slow circle. ” Where are you? What’s going on?”

“The valent is using us to relay and amplify its thoughts to you,” came the slithery voice of the Breth.

“Where is it?”

“We are unable to locate it….”

“The Breth are lying,” said my father’s voice.

“They can’t lie, Dad,” I said.

“Their lives are lies.”

“They can’t even grasp the concept of lying,” I insisted.

“Then they bend the truth. They are masters of rhetoric. You remember what that is, don’t you, Artistotle?”

He called me Artistotle. If Dad was already dead, as the Breth had told me, then how come it sounded just like him? I directed my question to the Breth, but it didn’t respond.

I marched on gamely. The door of the house was open when I got to the hilltop. I tried to ignore my pounding heart and rasping breath – to not be tired – but I felt like I was going to fall over.

The Breth was standing in the kitchen twirling like a corkscrew. “This dwelling is empty,” it told me.

“Where’s Jan?” I asked.

The alien responded with the mental equivalent of a shrug. “Not here.”

“How can you not find them?” I shouted. “You can read its mind….”

“All our senses tell us that it is here. Right where we are standing.”

I smelled the gasoline, just before I felt the heat coming up through the floor.

“The basement! There’s a fire in the basement!” I yelled as I turned and ran for the front door. It never even occurred to me that Dad had made a bomb until it went off, the impact launching me out the door and through the air to the centre of the driveway. I landed on my shoulder and moaned with pain.

I didn’t realize that the Breth had survived as well until pain of a whole different magnitude hit me in a wave from behind. The searing heat had bubbled the alien’s flesh and I felt every inch of it. As I turned and looked back at the house, I saw the Breth, still more-or-less alive – a monstrous amoeba squirming and flowing down the steps.

And I wondered for a moment if the creature was going to die; before I understood that the valents inside it would simply not permit it to give up. It wasn’t even feigning speech anymore, just filling me with information. I knew that the uncompromising will of the valents inside the Breth would speed repair of the tissue to mere hours. I understood that this was far from a fatal injury for a Breth and wondered briefly how Batch 4320 Prime had managed to die.

As I framed the question, I knew that getting caught within the inferno would have damaged it beyond repair, without necessarily killing its valents.

Then I saw Dad. He must have gone out the basement door and circled around the house. He came around the far side of the garage, carrying a pitchfork, walking straight towards me, hefting the implement like a spear. Every muscle in my body hurt, but I managed to get to my feet and turn to face him. I didn’t feel like I had enough coordination to dodge out of the way, but I was prepared to fight him anyway.

I was surprised as hell when he walked straight past me and plunged the pitchfork into the puddle that was the Breth. Alien flesh rippled and flowed up the wooden handle of the pitchfork which nailed the Breth to the ground. Then it stopped moving and just lay there, quivering.

After the initial jolt of pain, I heard and felt nothing more.

“Is it dead?” I asked aloud.

Dad shook his head and walked back past me, kicking open the garage door and stepping inside. His thoughts were no longer being relayed by the Breth, so I knew the thing must be hurt pretty badly.

“Where’s Jan?” I shouted to no one in particular. Unsurprisingly, no one answered.

From the garage came a roar and Dad stepped out, wielding a chainsaw. When he started walking back toward the Breth, I picked up a rock, which was the only weapon I could find, and blocked his way. He lunged at me, swinging the heavy tool so awkwardly with his single arm that I was able to jump out of the way. But I fell and smashed my own ankle with the rock. Through the pain haze, I could see Dad looming above me. And from my ground level vantage point, I could see something he didn’t – a fluid limb extending out of the fleshy puddle and coiling around Dad’s ankle.

The Breth pulled Dad’s legs out from under him. He lost his grip on the chainsaw, which carved up soil inches from my face as it bounced and twisted over the stony ground and finally stuttered to silence well out of Dad’s reach. The Breth’s tentacle pulled him into the centre of the puddle and the yellow skin of the Breth flowed over his legs like an oily sheet.

“Help me, Buffalo Bill!” The voice came back into my head. “You can save me. Use the chainsaw. Stop the Breth. They’ve come to enslave us all. Please!”

The Breth covered him like a glistening blanket.

I stared at the slimy, writhing cocoon. Through the pearly, translucent flesh, I could see the outline of my father’s face, his open mouth a small crater on the smooth surface, two smaller hollows for the eyes.

“Can you get the valent out and keep my father alive?” I demanded, pulling my hunting knife from its scabbard on my belt.

The Breth did not respond.

Gently but insistently, I pushed the tip of the blade into the Breth’s flesh, into the centre of Dad’s mouth. Yellow goo oozed out, more like tree sap than blood.

“Can you keep my father alive?” I repeated. Again, no answer.

I cut through, careful not to push it in too far I turned the blade sideways, preparing to cut open the sticky envelope, and pull my father from within, but his head burst out through the tiny opening like an eager newborn, already screaming.

The Breth screamed as well, its pain pouring into me from wherever I touched it, searing into my mind and down through my body – as though my own flesh had been torn open. Its thoughts were fractured, semi-coherent, bordering on delirious.

My father was shaking yellow blood from his hair like a dog shouting, “cut them again – cut them to pieces!”

I wanted badly to believe that my father was still alive, but there was too much wrong. His eyes were as dull and depthless as stones. He spoke of the Breth in the plural – something Dad wouldn’t have known or bothered to do. In that instant I understood and accepted that my dad was indeed already dead.

So I did nothing more as the Breth’s flesh clenched back around him and Dad’s eyes bulged out and his mouth gaped. I turned my head away as the Breth pushed a pseudopod of flesh into his mouth and blood gurgled out around it. My dad’s eyes rolled back in his head, and he began to shake as if he was having a seizure.

I said to the Breth, “I won’t release you unless you destroy this valent. The one that killed my dad.”

The Breth’s voice was a whisper. “It is already inside us. The joining is too advanced.”

“It’s an evil little fucker and it deserves to die,” I pressed the blade against the alien’s flesh once again. “Spit it out – or whatever it is you do….”

I lowered the knife, since it knew I was bluffing. I wouldn’t risk killing it by cutting it again.

“The valent’s memories are a part of you now?” I asked.

“Yes.”

“Then tell me where my sister is?”

“She…wanted to be Florence Nightingale.” The voice in my head, the Breth’s voice, sounded just like my dad’s. “But I thought she should be Michelle Kwan.”

“Michelle Kwan?” I shook him. “What does that mean?”

“A ‘figure skater’,” the Breth’s suggestion crawled through my mind and down my spine.

I saw images of bloody mannequins, one of them with Jan’s face. Leaving my father’s corpse, I got up and ran past my burning house down the hillside, screaming her name.

I found her lying on the ground behind the house, still alive despite a ragged slash across her throat. I Tore off a piece of my shirt, rolled it up and put pressure on it, but had no way to judge how deep the cut it was. The ground was soaked in her blood.

“Sorry,” she muttered, blood bubbling at the corners of her lips, her voice little more than a whisper. “I couldn’t kill him.”

“It wasn’t Dad. You know that don’t you? It was the valent; the malice worm.”

“Yeah,” she acknowledged, gripping my hand with blood-slicked fingers. “Did you bring the doctor?”

A doctor might be able to save her. But instead, I had brought the Breth – one of the creatures responsible for everything that had happened, for everyone who had died.

And I had left it pinned to the ground.

If it died, two hundred and eighty nine malice worms would be released, almost certainly destroying whatever was left of our Earth. But it didn’t matter. It had already cost me everything I cared about.

Staring down into my sister’s beautiful face, I amended that thought. Almost everything. Jan was still alive.

“Don’t die,” I told her. I placed her hand on the makeshift bandage. “Don’t give up!”

I lifted her in my arms and carried her back up the hill. Remembering how the valents had prevented the Breth from dying, I said, “Get angry.”

Mentally, I shouted to the Breth. I’m bringing her to you. You have to help her!

But when I got back to the front of the still burning house, all I found was Dad’s body and a trail of yellow slime.

You can’t just walk away!

I can’t remember if I thought it or screamed it. All I know is that I got no answer.

The Breth was gone.

It took me two hours to get Jan to Windsor Stronghold.

Now I’m doing all I can to help her stay alive.

As my own bitterness and rage grow like a tumour inside of me, I stay at her bedside, feeding it to her in tiny doses. “They almost destroyed us all. As soon as they got what they wanted, they just went away. We meant nothing to them. You can’t let them win.”

Sometimes, I just chant, “You can’t die. You have to stay and fight.”

Of course, there is nothing left to fight but memories.

Some nights I still wake up dreaming of Dad, wearing a mask of flesh and speaking in the Breth’s voice. “They’re inside us all, Bruce Banner. Straining to get out.”

When he peels off the fleshy mask, it’s my face underneath. Dad calls me his valent – because of the maelstrom of confusion and rage trapped inside. Only – there is no shell between me and the universe. Give me the means, and their entire planet will be dust.

–end–