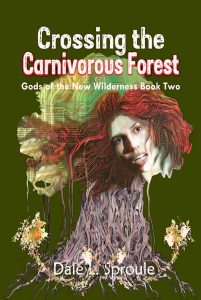

Except from Crossing the Carnivorous Forest

Chapter One: Sleeping in Brambles

A white bird burst out of the bushes as two girls walked along the path on their way home from the lake. Out of control, it arced straight for the taller girl’s face, blood spraying from a badly injured wing. Batting frantically at it with both hands, the girl known as Bo-Peep, because no one knew her real name, fell hard on her tailbone in the middle of the path and stayed there.

In shock, maybe? Bo-Peep stared at her hands. Words bubbled from her lips, which wasn’t unusual, but rather than her typical garble, this time it sounded like something real. Something significant.

As the thrashing dove got tangled in the tall grass beside them, Kasha crouched down to hear better.

“My sister used to call me the glump,” said Bo-Peep in a tiny voice. “Always told me how much she loved me, even while doing horrible things. Hateful things.”

Kasha, who had never heard their guest articulate a coherent thought, leaned in, astonished. Kasha followed Bo-Peep’s gaze into the sky as a low-flying hawk swept past, dissuaded from its prey by the presence of the girls as it arced back up and swung out toward the base of the Three Brothers mountains.

Thus distracted, Bo-Peep appeared to have lost the power of speech—or at least, the impetus.

Eager to keep her talking, Kasha prompted, “What kind of hateful things?”

Bo-Peep jerked her head back with a wild glare in her eye. The fury was gone when she looked back at Kasha, replaced by a wistful smile. “Not entirely hateful. Told me she could see my intelligence in the way my eyes flashed. Imagine that—flash, flash—bait to a hungry pike coming in for a bite.”

She leaned in as if sharing a confidence. “When they rescued me from the Carnivorous Forest, everybody thought I was dead. Brain dead. Nobody home. But my sister knew me, recognized me. She’d say, ‘C’mon Glump. That pesky kid is still inside you somewhere. Speak up!’”

“The forest?” Kasha asked. “What does this have to do with the forest?”

Ignoring her, Bo-Peep kept talking about her sister. “Always tried to answer her. I did. But the answers were hiding. I searched for them in the shallows, the shadows of the branches like swinging gallows. Hallowed, fallow, tallow….”

Kasha cocked her head, trying to make sense of what she was being told.

Blushing, Bo-Peep touched Kasha’s arm, tugging like a baitfish on the sleeve of her dress as she tried to talk herself off the ledge of rhyming words. “The crowd was huge, frenzied. Schools of them swam out from the rocks all at once, taking bites out of me, tearing the answers to pieces. Lost it all in a bloody daze. All the slippery, slickety answers swam away, swam away, swam away, gone.”

Having spent the last three hours fishing and catching nothing worth keeping, the metaphors all made odd but perfect sense to Kasha, who nodded, twirling her hand for her friend to continue even as she was again distracted by the dove, which had fallen to earth and now just erupted into occasional spasms.

Kasha stood, poised to tend to the creature even while fixed to the spot by the outpouring from Bo-Peep. Another distraction could spell the end of the narrative altogether. With furrowed brow she bent back down.

Bo-Peep said, “Dor would repeat things to keep me focused. ‘Zero in,’ she’d say. Dor zeroed in. She listened. No-one but her ever listened. She knew I was grateful. Heard me say, ‘Thank you Dor,’ and held me at arms-length and stared at me. ‘Glory?’ She knew my name. Glory, not Glump. ‘You really are in there, aren’t you?’ She hugged me. Hugged me? Yeah. I was worried there was a knife in her hand.”

Kasha dared interrupt. “Is that you? Are you Glory?”

Since the night Kasha’s father, Kemp, brought Glory home they had all called her Bo-Peep, something someone in the band had suggested. Lost her sheep. Lost her mind. Everyone went with it.

Now, suddenly, the girl was talking sense. Still a jumble but Kasha could puzzle it together if she listened hard.

“Glory, yah. Dor would brush my hair in the mirror. I’d get confused sometimes. Couldn’t tell us apart. She looks like me, but her face is rounder. She scowls a lot. Has a different nose. Button nose. Doesn’t unbutton, though. That’s good. Don’t want to see inside her head.”

“Dor’s head?” Kasha asked.

Looking at Kasha, Glory batted her big, hazel eyes with growing uncertainty. “But that was her. Dor, Adoris. I’m me. I think I’m me. Glory! Right?”

Kasha held up her hand. “Your sister is Adoris? The Executrix?”

“That’s right. And this is me, I’m free. Whee!” A song bubbled up.

“Hippity, hop-hop, hippity hop.

The fancy dancing never stops!

Bippity, bop, bop. Boppity-boom.

It zips across the room.”

After the singing stopped, more words flowed out. “Don’t just buy a broom, buy an Abraxas Vacuum. Vroom-vroom across the room. Scritch, scratch, 20 cats. An astonishing 182 cats per square kilometre in the Metro area. 182 squared is 33,124. Times 11 it’s magic. If you whisper ‘364’ 364 times, an evil mathematician will come down and lay his hands on you. Then poof.”

She made a ‘poof’ sound effect and smiled vacantly at Kasha, who supposed it was now too late to get her back to the earlier topic.

But this was something. More than a little.

This girl was the missing sister of Adoris, the Executrix, the most feared and powerful person in Hope—or anywhere, really. The Executrix of the Testator. There must be a big reward. Huge reward! Kemp and the band were playing some gigs up on Triple Creek at the base of the Brothers. She’d have to wait a fortnight ‘til they got home to tell them about this.

A corner of Kasha’s apron was still damp from fishing. Her hands were shaking as she used it to wipe the blood off Bo-Peep’s…no, Glory’s face, before wandering into the grass and putting the still-flapping bird out of its misery. She came back out, holding it by its feet. “A dove doesn’t have much meat, barely worth preparing. But we don’t have much to eat this week and it will add flavour to our pie.”

She reached for her friend’s hand and pulled her back to her feet. “Let’s go home. Then we’ll work out how to get you back to your sister.” With a shriek and a look of sheer terror on her face, Glory pulled her hand away, turning and running back the way they’d come.

As Kasha pursued her, she wondered what was causing these sudden mood shifts. The first one, the bird, made her open up in a way Kasha had never heard before—eloquent and strange as that minstrel fella, Tall Jeffty, who sometimes made rounds with Kemp and the band. But when it stopped, it left her in this jumpy manic state.

If Glory kept running at this speed, she’d reach the lake in minutes. At least there was a limit to where she could go from there.

However true that observation may have seemed, it took half the afternoon to track her down along the shoreline. In this time of the harvest moon, days were getting short and the mountain nights were too cold to stay out after dark without extra layers. Kasha found her friend crouched under bushes, staring out at the water, rocking back and forth and babbling claptrap.

Glory’s rocking stopped when Kasha sat down beside her.

“I’m sorry if I said something that frightened you,” said Kasha.

With a scowl, Glory shook her head and started rocking again.

Kasha pressed on. “You were telling me about Adoris and I…”

Glory sat down with a thump, locked Kasha in a glare and picked up a rock, half again the size of her hand. Kasha couldn’t say why it made her nervous. She didn’t believe Glory would throw it at her or hit her with it. But she also had trouble believing what Glory did with it, splaying the fingers of her left hand on the rocky soil and smashing her own fingertips. She cried out, clutching her injured hand to her chest, pushing Kasha back when she tried to help.

“Wackity-wack. Adoris came back. Always came back. Forty whacks squared. When I gave her one answer, she wanted the rest. All the answers in the world! When I couldn’t find them, she’d pinch me and poke me. Pinch and poke and pinch and poke until I screamed. She wouldn’t stop until I found the answers and gave them to her. And when the pinches didn’t work, then came the blades.” She bent over and parted her hair. “Always brushing my hair, telling me how thick, how pretty, how red.”

Wherever she parted it, Kasha saw the evidence—made more three dimensional in the late afternoon sun. What she’d thought was a skin condition was nothing so natural. The girl’s head was scored in a matrix of tiny scars.

“Oh, sweetie!” said Kasha, embracing her friend.

But Glory pulled away. All in one breath she said, “Pain makes focus. Blood makes it manifest night after night. Looking for answers ‘til she figured out how to fetch them herself then ‘Sorry, Glump, can’t let you uncork the secrets for anyone else. Imagine the anarchy if Deacon Kenosis or any of the elders dreamed they could continue the Reinvention without me?’”

“I’m sorry,” Kasha stammered. “Too fast. I couldn’t catch all that.”

Glory eyes went big and round and she said clearly, “The man she hired didn’t kill me like he was supposed to. Then your daddy killed him.”

She started singing a song that Kemp had taught them, about wrestling a grizzly bear. Jumping up every morning, ready to fight, even though you knew you couldn’t last. Until the bear was so impressed by your energy and determination it turned and walked away.

Kasha stared in wonder at Glory, who was now humming to herself, fidgeting and peering out at the clouds glowing orange and black as they roiled above the still waters of the lake. Everything wavered in and out of focus as she struggled to process all the incredible details about Glory’s real relationship with her sister and who that sister was.

A certain resolve had already settled in her to keep Glory here—protect her, even if Adoris sent an army.

But it was not her decision to make.

Chapter Two: Roots of the Soul

Raine remembered everything now. Or at least the BioGrid’s reconstruction of him did.

The experience of reliving his own birth had disturbed him at first, the simple fact that he could do it reminding him that he was no longer human and his memories weren’t his own.

But the memories were inseparable from him now, every moment he’d ever lived, from both his human and arboreal incarnations were preserved and accessible in mind-boggling detail. Given the strict rules forcing the inhabitants of the daemon realms to isolate from one another, there was little else to do but navel-gaze.

Early on, he recognized the similarities between being born and going blind: the former involved coming out of darkness into a dazzling blast of light and sound, tiny eyelids so thin and translucent, he could see dark shapes drawing near and moving away. Then, after days of learning how to see, the shadows resolved into shapes and the noises into voices.

Blindness took the opposite trajectory down the same path—a flash turning to a fuzzy haze. The last thing he saw after looking away from the Pulse were moving shadows of the people he’d followed into the lobby of the building where his dad worked, their small voices subsumed by the pandemonium inside.

As he ascended the stairs to his father’s lab for the upload, the darkness grew absolute. One of the billions blinded by the pulse of dazzling light the sun had become.

Rebirth into the BioGrid was a whole different kettle of fish. Focus was perfect from the instant he opened his eyes and saw an owl in a lab coat. Doctor OWL! Who better to welcome him into his new life than the mentor who had watched over him all through childhood?

Doc had answers to all Raine’s questions except one.

“When can we contact my father?”

“The BioGrid has not been connected to the outside world for some time,” the virtual mentor intoned with a slow, 270o shake of its head. “We have no record of his death, but if he were still alive, he would be more than 300 years old.”

Doc tried to salve Raine’s shock with more explanation. “The human population on Earth was so dependent on computers that they found themselves without the means to farm, harvest, and distribute food. The mortality rate was off the charts.”

“So, everyone just starved to death?” Raine wasn’t sure he’d said it aloud.

With a reprise of the creepy, slo-mo headshake, the owl said, “During the first pandemic, people broke into infectious disease labs looking for a cure. Instead, they released three more deadly pathogens in several different incidents. They found no cures for any of them.”

Owls don’t hang their heads. But that was the posture Doc assumed. And that sad news was but a fragment of what it shared as the relationship between Raine and Doc grew and changed over the years and decades.

The transformation of the vast bio-computer into the modern-day BioGrid became as familiar to Raine as his own birth.

Doc had collected the networked experiences of the forest into an anthology of metamorphosis, giving Raine the opportunity to live through every moment from dozens of different points-of-view, his own voice joining the psychic scream as the intense cosmic rays of the Pulse poured through the hollow cores of the banyan boles, from the buds on the branches to the tips of the tap roots, the solar particle bombardment erased as it descended. Raine’s consciousness became part of the chaos; the churn of senseless data that survived in pockets, recombining and repairing itself as best it could, but changing the essential nature of the BioGrid in the process.

The once monolithic consciousness fragmented and as it coalesced, divided into opposing factions. Where once all the knowledge of the known universe was available to Raine, his new reality was defined as much by what was withheld and denied. Universal access was no longer the de facto state.

The Core, which housed the administrative functions of the original system, discarded all pretense of humanity, settling on a definition of itself as a computer designed to serve humanity. The Core didn’t aspire to anything beyond finding the human Operator to give it purpose and lead it to fulfillment.

The Core rejected the Free-Thinkers’ central belief that they were humanity’s designated heirs and outlawed the virtual adoption and reanimation of the personas of humans from throughout the history of civilisation. They also dismissed Doctor OWL’s entreaties that Raine, having once lived a human life, must indeed be their long-sought Operator.

The factions did manage to cooperate as the BioGrid figured out how to use their motile rootlets to interface with all manner of creatures: insects, squirrels, raccoons, birds and other woodland creatures became their eyes and ears in the physical world. But it was a complex process and, in the course of mastering it, they killed off or shortened the lives of almost all their subjects.

The BioGrid’s first attempt to interface with a human—a child named Glory—went disastrously wrong—overloading the child’s mind to the point where she could no longer find the touchpoints in the sea of random data, wherein she had mentally drowned.

Convinced that they had destroyed their own precious Operator, the Core put the project on indefinite hold, even as interfaces with woodland creatures grew less lethal. Fifteen years later, in a debate that was live-streamed to the entire BioGrid, the Free-Thinkers redoubled their efforts to convince the Core that, as resurrected son of their creator, Raine Naidu was destined to be Operator.”

“Not long ago,” replied the Core spokespersona, “that may have been true.” It left a lengthy pause for dramatic effect before delivering the coup-de-grace in a discernable ‘how-d’ya-like-them-apples’ tone of voice. “But our real Operator has just stepped forward. Her name is Adoris.”

Refusing to recognize that the trees had any rights at all, Adoris pursued her personal agenda with relentless vigour.

When the long-brewing revolution manifested, Raine found himself as its leader.

With far less conscience than the trees, Adoris quashed the rebels, commandeering the Core’s authority to drive the revolutionaries underground into daemon realms that turned out to be prisons of their own making.

Having led the Free-Thinkers into purgatory, Raine dreaded the possibility that they may be stuck here until the forest petrified around them.

Chapter Three: Alternatives to Pathos

.

Half-expecting to find that having her sister killed would leave a glump-sized hole in her life that would be impossible to fill, Adoris discovered just the opposite.

Getting rid of Glory had made her life simpler and more interesting.

She nodded and closed her eyes to count her blessings.

Benefit one; the peace of mind she gained from no longer having to worry about keeping the source of her wisdom a secret gave her a better perspective on establishing priorities and planning for the future.

Benefit two; no longer needing to decode an encyclopedia worth of daily babblings to glean a trickle of information, left enough time in each day to enjoy a life beyond babysitting!

Benefit three; she no longer had to see or experience regular reminders of the harm and duress she inflicted on the only person in her life she had ever felt close to.

Guilt didn’t bother Adoris—as much as the lack of it. Her pervasive numbness was a constant reminder of how different she was from normal people. How excluded. How alone.

For the most part, she didn’t give a damn what anyone else thought of her. But there was also a part of her that craved their company, love, respect…even adoration.

Why devote myself to lifting humanity back out of the dark ages when I barely feel human myself? That’s not just ironic, it’s ridiculous. Pathetic.

And yet, her achievements spoke for themselves. She was the Executrix—the first woman to reach that position of absolute authority since the Testator had shone His light to guide his flock into the great beyond, leaving everyone else to fend for themselves.

And having figured out how to interface with the forest, Adoris had also become the Operator, the human representative the BioGrid had been created to serve. Nothing in her life was coincidence; it was a convergence of opportunities and clear messages. She was the true heir to the Testator’s estate on Earth and all her subjects and followers were her beneficiaries. Ambition was one of the tools she had been blessed with. It enabled her to fulfill her destiny and responsibility of restoring humanity to its former supremacy.

Adoris rubbed her face with the palms of both hands. It wasn’t a fault of her character that the glump’s absence didn’t stir up any guilt at all; it was an advantage to be able to move forward without that distraction. She needed to put it out of her mind.

Lying back on the interface bed she tugged on the tip of a rootlet to let Tree One know she was ready. As the first of her bonsais, it was the conduit she most often used to move data back and forth between her and the BioGrid. Today, she had a specific goal.

One of Ephrem’s reinvention teams was trying to get video screens working again. The BioGrid’s instructions had taken them to the verge of another breakthrough—a working model of one of the more advanced LED systems.

But instead of bringing the organic diodes back to life, all they’d managed to make visible on the screens in the lab were what looked like masses of puffy grey slugs squirming in a glass box. This was a big improvement from the black screens they’d started with, and even the blizzard-at-twilight static a few months ago, but still woefully inadequate. It was possible, if not likely, that the hues and flashes of colour she had seen amongst the vague shapes were no more than wishful thinking.

Adoris’s enthusiasm was becoming as muted as the colours.

This was a tricky fix that might require chemicals and substances Adoris didn’t keep on hand. In addition to stretching her resources, refining the yield from her mining operations into anything useful often required learning even more new technologies.

This time, the BioGrid suggested a simpler solution and presented her with a folder full of shipping manifests suggesting that a shipment of the cutting-edge LED transmitters they had been seeking may have survived in a warehouse in Aggasiz. The Core made a convincing argument that the item they were looking for would have been seen as worthless to scavengers, little non-functioning plastic gizmos with no discernable use. With thick, molded plastic packaging protecting them from decay, some may well have survived.

The upload of the manual and technical specs into Adoris’s brain had already begun.

In order for Ephrem to create real-life prototypes, he needed precise instructions. And the technology she needed to pass along to him was far from simple.

Since they did not have the tools and raw materials at the Tomb to create the components they needed, she had to teach Ephrem and his staff how to distinguish, test and install salvaged coils, chips, transistors, capacitors, diodes, oscillators and so much more. Any missing details could doom a project to failure.

As the information she was attempting to transfer grew more esoteric and complex, the task grew beyond her. Too much essential data bled away in the process of transference.

When she had related those concerns to the Core council, they came up with a solution, sending her to the BioGrid databank to train in file storage, organization and retrieval. Adoris was an excellent student. This new technique enabled her to retain enough relevant details to cut the number of interfaces required down to one or two per project.

But recently she had started experiencing a negative effect. The adjustments in her perceptions were allowing real-world memories to be displaced by technical data. She started forgetting things she should remember and remembering irrelevant things she would rather forget.

Mathematical formulas that swirled through her brain would occlude more mundane and essential information like memories of day-to-day interactions and the words she needed to communicate the knowledge she had gathered.

She had intended this interface to be short, in order to reduce the havoc that her time in the BioGrid was starting to play with her memories back in the real world. But had already gone well beyond her self-imposed limit.

When the interface terminated, Adoris lay motionless, head throbbing from all the stuff she was struggling to remember.

As Adoris shook her head, trying to get her bearings, ghosts crawled out of the fog. She saw the glump being pulled, bleeding and catatonic, from the woody clutches of the Carnivorous Forest. It was more than a memory; it was like she was reliving the day.

As the panic of the rescue team had turned to excitement when they discovered that the little girl was still alive, everyone assumed that Adoris was crying tears of joy or relief, when they were, in fact, just a manifestation of her overwhelming fear that her own role in the tragedy would suddenly come to light.

She thrashed on the interface bed, struggling to hold in a scream. How could something from so long ago feel so vivid and immediate?

She had long since hidden those memories and intense emotions away, locked them in an unlit chamber of her back-brain from which she had been certain they could never reemerge.

And now this.

After Glory was born and became the centre of the universe for all the butt-kissers and sucker-uppers in the Tomb, the seven-year-old Adoris had come up with methods for deflecting some of the limelight back at herself. Adults liked when she hung on their words and were impressed when she demonstrated how intently she could listen. Some of the questions she asked were as deep and relevant as anything these people were asked by other adults, including their fellow members on the Council of Elders. They all praised her and that pride left a warm residue in her chest that melted away slowly.

Whenever Adoris glowed with self-satisfaction, everyone near her felt the warmth.

Shame, on the other hand, was an emotion she found unbearable. Shame made Adoris’s nerves jangle and awakened a hundred shades of melancholy. It crawled into her back brain and made nests there. In shame, she would curl up and squeeze her belly as it ran a slimy skein of arms around her.

And the very worst effect of the heightened memory was the way the moment of her greatest shame remained on permanent replay in her mind.

While her mother was a super-sensitive soul always in search of ways to numb herself, to damp down the intensity of everything, her father had seldom shown his feelings.

Mother had locked herself in a closet of borealis powders and dreamed a world where her babies frolicked without care. But Adoris’s father was unafraid of taking his daughter to task.

Following Glory’s rescue, he’d made Adoris wait for hours in his office full of pain inflicting instruments before returning with his update and verdict. The whips on his office wall smelled of lavender oil and the nuts on the thumbscrews on his desk glittered with jewels like the wings of butterflies.

“Because beauty helps soothe the pain,” the Executor explained.

Accordingly, she tried to think of wildflowers but smelled only the manure they grew so well in.

The fear, the endless drama, and ennui of waiting to hear about the fate of the glump already had Adoris unbalanced.

Everyone around her seemed to have bought into the lie she’d used to save herself from taking responsibility for the toddler’s disappearance; a masked kidnapper who had scooped up the child and carried her down the mountainside, somehow going under the fence and disappearing into the underbrush.

Guilt and repentance were the cornerstones of their faith and Adoris’s father was skilled at finding the means and the fortitude to elicit the atonement required to exonerate all the penitents and criminals who came to him.

Shortly after accepting the job, he had confided to Adoris, “With the right incentive, you can make anyone confess to anything. If they’re guilty, it’s even easier.”

Adoris had waited in her father’s office for what seemed much longer than a single day. Time had come to a stop as everyone waited for Glory to awaken.

The last candle in the room was guttering by the time the door creaked open.

The light flared to relative brilliance as Father lit a fresh taper and proceeded in his own personal globe of light. He sat down in silence and picked wax out of the candleholder so he could put the new one in before looking up from the task, his gaze so flat it failed to bridge the gap between them as he looked toward her eyes.

Thinking it better to break the silence than remain suspended in ignorance she asked. “How is Glory?”

He shook his head. “Not herself yet. And whether she ever will be again remains a riddle. We have not found any witnesses to corroborate your claim that she was abducted.” He paused to frame a question. “Was your man in black inside the Tomb? Or did he somehow enter from outside?”

The futility of lying to the Executor was an article of faith at the Tomb. But Adoris had done it before without repercussions and felt quite pleased with her cleverness. This time was different. The look in his eyes said he saw through her lies.

Her status as the Executor’s daughter had always sheltered her from the mortification that befell other penitents. Surely, her own public and excruciating execution was imminent.

“I love you more than all the stars in the sky,” Father had once told her.

Now, in Adoris’s imagination, the stars streaked as they fled the firmament.

She felt terrible about betraying a confidence, but it seemed the easiest way out. She heard herself suggesting, “Nurse was with a man. It might have been him I saw.”

Her father perked up, seeming to recognize the scintilla of truth in what she said. He seemed more relieved than curious. “She was with a man. Why didn’t you tell me this before?”

She shrugged. “I got used to him being there. He was one of the guards.”

“Do you know his name?”

Adoris winced and nodded. She had no friends, but both the guard and the nurse had been kind to her.

“Is it over?” Adoris asked her father after he showed her their bodies.

“They both confessed,” he said. “It satisfied the Council of Elders. But you and I know that their outcome has no bearing on the nature of your negligence.”

The air grew so warm and stale that the deepest breaths couldn’t fill her lungs. She squeaked, “What do you mean?”

“This relationship between the guard and the nurse. How long was it going on?”

Adoris shrugged.

“I’ve… ‘spoken’…to the chambermaids. They all conceded that it had been going on for months. How could you not notice that?”

Adoris couldn’t even bring herself to look up as his voice continued in a suggestive murmur. “You often took advantage of their…preoccupation.”

He curled his fingers under her chin and lifted her head, so she had no choice but look in his eyes, which seemed moist, almost teary. “Didn’t you my dear?”

His accusation was sharp as a knife.

He pulled his hand away and sat up straight. “This guard was too busy pursuing his carnal objectives to go around abducting children. It was you who took your sister outside, didn’t you?”

Each sentence, each word deepened her horror and humiliation until it could go no deeper. As though the floor had dropped away into a sea of fire, the skin on her face felt scorched. She closed her burning eyes.

Her belly churned like it housed a live eel in a boiling pot. Her palms were sweaty, her breathing shallow. Her skin prickled and her shoulders ached. She wanted nothing more than to disappear—to be anywhere but here.

“No.” Adoris shook her head, whispering. “I didn’t take her out. She followed me. I told her to go back.”

“She couldn’t open a heavy door like that herself,” he said, eye’s glittering like the jewels in the wings of the thumbscrews.

“If I had closed the door behind me,” explained a snuffling Adoris as she struggled to find the words, “I wouldn’t have been able to get back in.”

If he had looked at her with disdain, she might have been able to bear it, but the look he gave her was filled with grief and betrayal. His usual stony façade crumbled as he too began to cry. “In the absence of the Testator, I was elected to uphold the truth in His stead. The people of Hope have faith in me.”

He swallowed hard and his lips curled into a sneer. “If they saw what an entitled, self-obsessed, little liar I have spawned, it could jeopardize everything I have worked so hard to achieve, everything I hold dear. It would undermine my authority, and worse—my integrity.”

Her mouth opened and closed silently, and she retreated inside herself, a huge door slamming after her. One moment, she was devastated—so ashamed that she thought she’d never be able to look anyone in the eye again. In an instant, calmness was restored.

It was the last time she felt shame. Or much of any emotion. If she couldn’t depend on her father to be the rock she needed, then she must be the rock.

She heard herself saying, “As my penance, I propose to singlehandedly care for Glory until her condition improves. When you see my self-sacrifice, you will be proud of me again.”

Her father shook his head, contempt escaping in a huff. “That sort of work is what nurses and servants are for.”

Adoris nodded. “But you’ve just shown the world that they can’t be trusted. What you need is a child who is beyond reproach. And I shall be that child.”

Adoris didn’t believe in the value of penance the same way her father did. In her opinion, when the Testator abandoned humanity, any debt they may have at one time owed must have fallen away with Him. As had their guilt.

It was a relief when Father nodded. Despite the circumstances and notwithstanding all that had just transpired, a smile played at the corners of his lips.

Many times, over the following years, she’d stare at her hands, with their nails cut to the quick so-as to gather less shit while changing Glory’s diapers, and wonder if she’d made the right decision.

For those first years, the one person available for Adoris to talk to about it was the glump herself, sitting on her rump, spitting out food and crying.

Even with a staff of nurses and housekeepers to do the heavy lifting and much of the dirty work, Adoris was trapped. Perversely, the glump’s helplessness just made her more inescapable. With a newborn’s brain in her growing frame, Glory was a weight that got heavier with time.

To keep reading – visit Godsofthenewwilderness.com and hit the “Buy Now” button to choose your preferred retailer.